Listen to audio transcription here or scroll down to read

Introduction

This is an article about autonomy and instincts through the lens of being autistic and/or living, working and being alongside autistic people. In the first part of this article I share a story about a very short but significant interaction between myself and a young person I once worked with. This story helps demonstrate the link between the ability and opportunity to follow our instincts and practicing autonomy. This link might not be initially clear or obvious, but I hope this article will change that whilst demonstrating the importance of the relationship between instincts and autonomy from an autistic perspective. The second part of the article covers seven principles that we can use to prioritise, value and enable Autistic Children to practice autonomy.

Autonomy itself is a complex term which can carry many different meanings. Because of this I’m not sure it’s always the best word, but it’s the one I have! The autonomy I’m talking and thinking about here has two parts, both necessary for it to exist, I will define them as;

1. Having access to the knowledge and learning you need to have control over your actions.

2. Your needs and wants having equitable status in your community and wider society.

Thinking about instincts

About seven years ago I was sat in the back of a mini-bus full of 8-12 year olds, all of us seemingly tired but wired following a trip to a warehouse full of trampolines. I was chatting away with the child who was sat next to me; reliving top bounce moments, joking and laughing. We got to a part of the story that involved another child who was sat in the seat in front of me, I called out his name to get him involved and, without a moment’s hesitation, he responded loudly and clearly with; ‘Oh, Shut your face!’.

Seven years later I still look back on this often and fondly. To me it’s a story of a young child asserting their autonomy despite existing within cultures and systems that work to suppress it. As an autistic child there are often extra and specific layers to this suppression. For me, understanding this and then being able to support that autonomy begins with thinking about instincts.

Autistic children often get taught to ignore their instincts. When a child is told they must keep their hands still when every part of their body and nervous system is telling them to wiggle them. When they are told they have to hold hands in a circle with other children even though the sensation is unpredictable and at times unbearable. When they are told ‘not to be silly it’s not that bad’ when a sound or taste is making their head melt and insides shiver. When they are told that if they don’t look someone in the eye then they are not being truthful even when they don’t actually understand how to lie and looking someone in the eye feels sharp and painful. When they are repeatedly seen as being in the wrong socially… told they are being silly or anti-social or unkind because they need space or time or just a bit of positive regard from others because they do things in a non-typical way.

These are all things that happen frequently and can be seen as pretty innocuous to the majority. But these are all things that dismiss the needs and often physically, sensorially and emotionally challenging experiences of the autistic child in systems and environments that aren’t built for them. They happen from an early age and come from many directions, from adults and sometimes children and perhaps most notably within education. As this dismissal and taught-ignoring or supressing continues and happens over and over it builds into something much bigger and becomes the way a child just exists in the world.

I interpret these acts of dismissal of the child’s instincts as a meeting of two things. Firstly a lack of understanding of the experience of autistic children and secondly, an often unexamined and deep drive for compliance between adult and child. It is often the children whose needs differ the most from the majority that get the most demand for compliance put upon them. Of course there are times when ignoring your instincts might be important, sometimes it’s necessary to stay safe. But this should be the exception not the rule. Being expected to constantly override your body and brain based on someone else’s assumptions and expectations is highly damaging and unnecessary. Particularly so when it happens during the time where you are building the foundations of how you understand and move through the world. Yet this is happening all the time for autistic children.

What happens when we teach a child to ignore their instincts?

The child who told me to ‘shut my face’ was joyful, kind and thoughtful. Going to a mainstream school he didn’t have many autistic peers. He was used to bending to others and very concerned with not being ‘annoying’ or upsetting anyone. He remains one of the funniest people I’ve ever known. When we were bouncing off each other he’d sometimes do a double take and say ‘why on earth are we like Monty Python right now’. I suspect his slightly off-piste humour was a useful tool for him socially. He was able go along with things whilst still finding a way to be himself. He would very likely have been described as ‘polite’ and ‘grown up’ by the adults around him… which may have made it difficult for them to see where he struggled and how much he had to work. He was not someone who asserted boundaries for himself. So the “shut your face” came as a pleasant surprise.

So what are the implications of this experience… when a child is taught to ignore their instincts what processes are these children missing out on?

They are missing out on learning how to recognise their instincts and this recognition is what enables us to make connections between our emotions, bodily feelings and actions.

They are not getting to explore what those instincts mean. This exploration is what allows many of us to figure out the differences between wants and needs, weigh up risk and benefit.

Having done that recognising and exploring they are then not getting to express those instincts which is an act that can allow us to feel seen and understood, connect with others through shared wants and needs and gain a deeper understanding of how those needs might clash with others.

They are not getting to follow those instincts, an act that allows us to develop our sense of self, expand our understanding of the world around us, express ourselves freely and genuinely and feel safe and respected. Instead of getting to explore or feel out any of this richness, they learn to ignore them instead.

Doing this repeatedly over a period of time means losing access to all of these processes. I’ve spent time with a lot of fellow autistic adults who are trying to learn them now, often having repeatedly found themselves in vulnerable and damaging situations.

Linking instincts to Autonomy

Here’s why this “Shut your face!” felt so big! For this child it was a product of doing at least some of these things. It happened in a split second but he was recognising what he needed; to not have verbal demands placed upon him. He was able to ascertain that it was safe for him to assert that need and then he was able to express it. In a way I’d never heard or experienced him doing so.

Now, personally I’m not offended by being told to “Shut my face” if, well, someone needs me to shut my face. But I appreciate that this might not be ideal in certain circumstances and to certain owners of faces. Because of that in many situations this child would have been reprimanded… but what is more important here; politeness or a child expressing and asserting a need? If this child had more access to the latter, more positive experience built up over time leading to more opportunity to develop tools and practice using them, then perhaps there would be time to think about the former. But this is not the case for many autistic children. Depending on where that child is starting from it might be appropriate to explore ways to express and assert their needs in ways that are considered more polite or appropriate, and therefore might help them get listened to in certain situations. However the capacity to assert need should be prioritised.

Being able to engage in all these instinct based processes is part of having autonomy. To return to my earlier definition the Autonomy I’m discussing requires the presence of two things;

1.Having access to the knowledge and learning you need to have control over your actions.

2. Your needs and wants having equitable status in your community and wider society.

Autonomy and how we are taught to engage with our instincts are tightly entwined. As such the lens of autonomy is a useful one to use to address the idea of allowing autistic children to engage with their instincts.

How can we approach such a big and broad idea? Often we approach it by thinking about how to ‘give’ autonomy to people. I think this can be a step backwards as a starting point. Autonomy is something that develops within us as we grow and experience life rather than something to be gifted by others. However many people, in this case autistic children, are subject to the systems, structures and people around them actively taking that away. Therefore rather than thinking about ‘giving autonomy’ I feel its more helpful to think about and act from a place of intending not to take autonomy away. This might also look like allowing that autonomy to bloom, giving someone permission in different ways and practicing generosity in how we relate to people who are going through this process.

I’m going to share seven principles to make space for capacity for autonomy to flourish in autistic children and help prevent us from taking it away. These principles are of course, applicable and useful for all children, but have arisen within specific context of autistic children as I’ve outlined above. A caveat for these is that, there may of course, occasionally be times where these need to be overridden, usually in the case of the safety of the child, but this should be a rare exception.

Seven Principles for Valuing, Prioritising and Enabling Autistic Children’s autonomy

1. Give an ‘out’ whenever possible.

1. Give an ‘out’ whenever possible.

When offering children activity and interaction make sure there is a way for the child to choose not to engage; to say “no” or “not now”. Based on that child’s experience in the world it is not a given that they will automatically be able to do this for themselves and they may need support to figure out how to express these “no’s” and “not now’s”. Or they may be expressing them already and you might need support in being able to recognise what that “no” or “not now” looks like. They might be verbal, touch, gesture, a turning away of the head, a pushing away of an object, sitting on the floor and not moving. The child may have developed “no’s” and “not now’s” that offer challenges to those around them. They may have learnt that adults around them only respond to their “no’s” and “not now’s” when they are aggressive or disruptive or even dangerous. This doesn’t mean we don’t listen. In this case listening is perhaps the first step to helping that child feel safe enough to develop new ways of expressing these needs.

From here it’s important to make sure you leave enough space and opportunity for that child to then use their “no” or “not now”. This might simply be leaving more time between interaction and offerings, it might be a verbal or physical prompt or it might be telling a child what you are going to offer, giving them some processing time and then offering it. There are many possibilities for what this looks like but developing this communication with the child and then paying respectful attention to it is fundamental. It deserves all the time it needs.

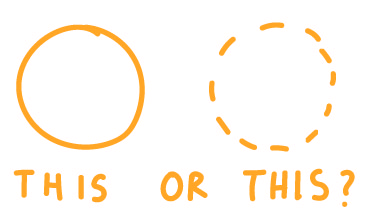

2. Don’t offer choice when there isn’t any.

I see this happen a lot, children are verbally offered a choice where the outcome is already set. I think it often comes from a feeling or desire on behalf of the adult to give choice and make sure the child feels heard and respected, but being in an environment when there is not actually much flexibility. For example in a school setting asking a child ‘do you want to come and do maths now?’ in an enthusiastic and cheerful manner when actually, you are saying ‘you need to come do maths now’. (I’m not here discussing whether this should or shouldn’t be how things work that’s a whole other essay!). When that child says “no” and the adult then has to tell them to go do maths now, they experience being seemingly offered a genuine choice and then their choice being ignored. Or perhaps you are supporting a young person out and about and you ask them if they want to “stay in soft play or go get a hot chocolate” when you actually need to leave the soft play but are hopeful or pretty sure they will choose the hot chocolate. If that young person then opts for soft play, again, they’ve seemingly been offered a choice and then had their choice ignored. These may both seem like innocuous low stakes things but as it keeps happening they build into something much bigger and the child expects their choices not to be respected. I’ve also seen this happen on much higher-stakes scales, for example disabled autistic adults being offered a choice about where they might live or spend their time, but this offering of choice is not real.

I see this happen a lot, children are verbally offered a choice where the outcome is already set. I think it often comes from a feeling or desire on behalf of the adult to give choice and make sure the child feels heard and respected, but being in an environment when there is not actually much flexibility. For example in a school setting asking a child ‘do you want to come and do maths now?’ in an enthusiastic and cheerful manner when actually, you are saying ‘you need to come do maths now’. (I’m not here discussing whether this should or shouldn’t be how things work that’s a whole other essay!). When that child says “no” and the adult then has to tell them to go do maths now, they experience being seemingly offered a genuine choice and then their choice being ignored. Or perhaps you are supporting a young person out and about and you ask them if they want to “stay in soft play or go get a hot chocolate” when you actually need to leave the soft play but are hopeful or pretty sure they will choose the hot chocolate. If that young person then opts for soft play, again, they’ve seemingly been offered a choice and then had their choice ignored. These may both seem like innocuous low stakes things but as it keeps happening they build into something much bigger and the child expects their choices not to be respected. I’ve also seen this happen on much higher-stakes scales, for example disabled autistic adults being offered a choice about where they might live or spend their time, but this offering of choice is not real.

3. Praise and acknowledge assertion of need- regardless of outcome.

However skilled and comfortable a child is in expressing what they want and need, there will of course be times where they don’t get it. Hopefully this is when we are talking about wants and not fundamental needs. When this happens it can be valuable to acknowledge that this has happened. It can help distinguish these times from ones where their assertions are ignored or missed. You can praise how a child has expressed themselves, be clear that you have understood and also acknowledge that yes, it can really suck when you can’t get what you want. This can be as simple as saying ‘I know that you don’t want to leave the park but we have to right now’ or ‘I can tell you are upset that she doesn’t want to play with you, it’s okay you are upset but you still need to leave her alone’.

However skilled and comfortable a child is in expressing what they want and need, there will of course be times where they don’t get it. Hopefully this is when we are talking about wants and not fundamental needs. When this happens it can be valuable to acknowledge that this has happened. It can help distinguish these times from ones where their assertions are ignored or missed. You can praise how a child has expressed themselves, be clear that you have understood and also acknowledge that yes, it can really suck when you can’t get what you want. This can be as simple as saying ‘I know that you don’t want to leave the park but we have to right now’ or ‘I can tell you are upset that she doesn’t want to play with you, it’s okay you are upset but you still need to leave her alone’.

4. Focus on enabling children to have control of their bodily and sensory experience.

For a lot of autistic children, the way that their sensory systems work differs from the majority and therefore the ways children are typically encouraged to explore and understand their sensory experience might not work the same way for these children. The world can be a scary place when you experience discomfort, pain, overwhelm or confusion in response to stimuli that others seem to find innocuous, exciting, or pleasurable. Our sensory responses are highly instinctual and are amongst the instincts autistic children are often expected to override or ignore. Being supported to understand and then take steps to make that experience less scary and also open doors to enjoyable and chosen challenging experiences is important in developing autonomy. In order to understand and express our needs we need to feel safe to explore them.

For a lot of autistic children, the way that their sensory systems work differs from the majority and therefore the ways children are typically encouraged to explore and understand their sensory experience might not work the same way for these children. The world can be a scary place when you experience discomfort, pain, overwhelm or confusion in response to stimuli that others seem to find innocuous, exciting, or pleasurable. Our sensory responses are highly instinctual and are amongst the instincts autistic children are often expected to override or ignore. Being supported to understand and then take steps to make that experience less scary and also open doors to enjoyable and chosen challenging experiences is important in developing autonomy. In order to understand and express our needs we need to feel safe to explore them.

For example, a child who reacts in perhaps challenging, distressed or seemingly unpredictable ways to different noises when out and about might benefit from chances to explore making and listening to different kinds of sounds and noises in a low pressure environment at their own pace. This can then help them, and you, predict and understand what noises to avoid where possible, what noises are manageable if unpleasant, what ways there might be to improve these experiences as well as helping the child to understand noise and how their body reacts to it. It may also change their relationship with certain noises over time. This is not about ‘fixing’ the way they experience noise but giving them tools and opportunities to understand it which can then lead to less painful and upsetting experiences. It is not uncommon that children who really struggle with loud noises can get a lot of fun and enjoyment when they are making those noises themselves. These experiences can then help them cope with the times they are not in control.

5. Explain your ‘no’s, don’t expect children to accept and comply ‘just because’.

Repeatedly telling children “no” and not to do things without ever offering an explanation for why is a very common and unquestioned way that adults relate to children. It feels like a hangover from an era we’ve, in theory, tried to leave behind, where children are taught to be compliant over anything else. Now we value and encourage critical thinking in children in so many areas but still expect them to turn this off when it suits us. The message it gives is confusing, it tells children that their autonomy matters when it is convenient. Often where I’ve worked in mainstream school settings where autistic children are being seen as ‘challenging’ this is something they are pushing against. Sometimes with clear intention and sometimes with a true lack of understanding. A common trait of autistic cognition is an inability or difficulty in doing or learning something without all the information. Sometimes simply taking the time to offer some explanation for a child when making a demand on them can make a huge difference, reducing a lot of unnecessary friction and restriction of autonomy.

Repeatedly telling children “no” and not to do things without ever offering an explanation for why is a very common and unquestioned way that adults relate to children. It feels like a hangover from an era we’ve, in theory, tried to leave behind, where children are taught to be compliant over anything else. Now we value and encourage critical thinking in children in so many areas but still expect them to turn this off when it suits us. The message it gives is confusing, it tells children that their autonomy matters when it is convenient. Often where I’ve worked in mainstream school settings where autistic children are being seen as ‘challenging’ this is something they are pushing against. Sometimes with clear intention and sometimes with a true lack of understanding. A common trait of autistic cognition is an inability or difficulty in doing or learning something without all the information. Sometimes simply taking the time to offer some explanation for a child when making a demand on them can make a huge difference, reducing a lot of unnecessary friction and restriction of autonomy.

Part of autonomy is also having the chance to make decisions. Children need the information available to do that. Sometimes the explanation of a “no” might be “because it will help me”, “because we don’t have time” or “because it will keep you safe”. Sometimes the explanation might be “I don’t know exactly” and then there might be some reflecting to do about whether a “no” is actually necessary. When telling children ‘no’ for reasons of safety, as well as explaining why I’ve deemed something too dangerous or risky I’ve often added to the explanation that part of my job is to keep that child safe. I find this extra bit of information about why I’m the one telling them “no” is often helpful to the child in processing and understanding why I’m stopping them from doing something and that I’m not just wilfully asserting my dominance!

6. Share your own processes.

Remember that these processes are things you are constantly doing, most likely much more automatically then children you might be interacting with, but not necessarily with ease. A lot of adults, including autistic adults as described above, continually struggle with autonomy. Being aware of how you navigate this for yourself and then, where appropriate, letting children in on your processes can be extremely valuable. It can give permission to those children to do it for themselves, affirm that they are not alone in perhaps finding it a difficult thing to do and provide a model for them to try out. For example, if you’re with a child and encouraging them to try out some messy play and that child is unsure but curious, you can do it alongside them. As you reach into the bucket of jelly or gluck or foam you might narrate it; ‘hmm I’m not sure about this but I want to try it… ooh I like the feel, it’s a bit gross but I like it… its fun but I think I want to be dry now so I’m going to stop and clean myself up’. Or, perhaps a child is asking you probing questions about your appearance (I’m sure this is relatable to many!). I often get asked about my tattoos and why I have them and a lot of the time children will express that they think they’re a bad idea or will be confused about why I have them… I try to take this opportunity to say that it’s okay if they don’t like them, but I chose to get them because I like the way they make me feel and I enjoy seeing them.

Remember that these processes are things you are constantly doing, most likely much more automatically then children you might be interacting with, but not necessarily with ease. A lot of adults, including autistic adults as described above, continually struggle with autonomy. Being aware of how you navigate this for yourself and then, where appropriate, letting children in on your processes can be extremely valuable. It can give permission to those children to do it for themselves, affirm that they are not alone in perhaps finding it a difficult thing to do and provide a model for them to try out. For example, if you’re with a child and encouraging them to try out some messy play and that child is unsure but curious, you can do it alongside them. As you reach into the bucket of jelly or gluck or foam you might narrate it; ‘hmm I’m not sure about this but I want to try it… ooh I like the feel, it’s a bit gross but I like it… its fun but I think I want to be dry now so I’m going to stop and clean myself up’. Or, perhaps a child is asking you probing questions about your appearance (I’m sure this is relatable to many!). I often get asked about my tattoos and why I have them and a lot of the time children will express that they think they’re a bad idea or will be confused about why I have them… I try to take this opportunity to say that it’s okay if they don’t like them, but I chose to get them because I like the way they make me feel and I enjoy seeing them.

7.Create spaces where children can follow their instincts and interests.

Make sure children have plenty of time and space to explore their instincts, learn about them and play with them. This perhaps most organically comes in the form of affirmative, stimulating and child led play space. Space where children can follow where their attention goes, where they don’t feel pressure to play in a certain way and where they can’t fail, or where failure is part of the fun. The more of this space children have the more they get to practice autonomy and learn what it means for them. The act of preserving and creating this for children as adults also shows them that their instincts and therefore autonomy matters.*

Make sure children have plenty of time and space to explore their instincts, learn about them and play with them. This perhaps most organically comes in the form of affirmative, stimulating and child led play space. Space where children can follow where their attention goes, where they don’t feel pressure to play in a certain way and where they can’t fail, or where failure is part of the fun. The more of this space children have the more they get to practice autonomy and learn what it means for them. The act of preserving and creating this for children as adults also shows them that their instincts and therefore autonomy matters.*

Conclusion

Not taking away a child’s autonomy is a worthwhile and essential aim in itself. But it also frequently will lead to creating nourishing, connective and positive experiences. There’s a scenario I’ve experienced and heard many versions of over the years which demonstrates this beautifully;

You might be spending time with a child over weeks or months and every time you see them you might extend some invitation to interact or communicate with you. Each time, without any clear reason and in their own way that child will give you a “no”. You respect that no, but don’t let it dissuade you from extending that invitation again in the future. Then, one day, you do as you have many times, likely not expecting anything different, but with no clear reason why, the child gives you a “YES.” Suddenly the relationship shifts and possibilities open up. Where you, as the initiator, might have spent all that time experiencing being repeatedly rejected, that child has experienced being repeatedly listened to. Making sure to not restrict or suppress that child’s autonomy by listening for and then respecting their “no” and then taking steps to enable it by continuing to offer them a choice has created a moment of genuine and chosen connection from which more opportunities can follow and flourish.

*For more on this see my article ‘What we say when we prioritise Inclusive Play https://playradical.com/2020/07/16/what-we-say-when-we-prioritise-inclusive-play/)

Thank you to Sal for her sense-reading and editing help in writing this piece and thank you to every child who, in their own way, has ever told me ‘no’, ‘not now’ or even ‘shut your face’.